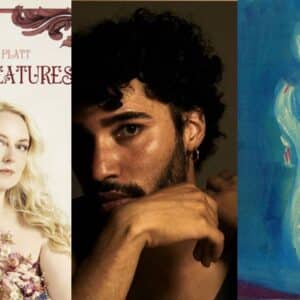

There was much talk once upon a time of a handshake that didn’t happen –and then did happen — at the Saarc summit in Kathmandu. It was quite some years ago. On the opening day of the summit, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistani Premier Nawaz Sharif did not say hello to each other, did not shake hands with each other. They simply ignored each other.

On the final day of the summit, at a retreat for the heads of government, Modi and Sharif did shake hands, did smile. But that was all too brief, a little too perfunctory. There is hardly any reason to think that the two men enjoyed the experience of finally linking hands. Perhaps by making amends at the retreat they were really trying to save face before the assembled media?

You might as well reflect on that question. And then you could go into some other historical stories about handshakes or the lack of them. Way back in 1954, Chinese Premier Zhou En-lai spotted the rabid anti-communist John Foster Dulles, then US secretary of state, at the Geneva conference. He decided to do what decent men always do. He stretched out his hand and began walking towards Dulles. Dulles, angry that China had slipped into the hands of the ‘Reds’, turned around and walked away. Zhou and everyone present in that hall were embarrassed. For all the embarrassment he felt, though, it was Zhou who came away morally triumphant. The world does not quite remember Dulles. It reveres Zhou.

And then comes the irony. Eighteen years after 1954, it was President Richard Nixon who travelled all the way to Peking (today’s Beijing) on a historic mission of reopening America’s links with China. When the door of the US leader’s Air Force One opened at Peking airport, a beaming Nixon walked down the gangway, hand outstretched, to be taken by Zhou En-lai at the foot of the stairs. In a moment that history has recorded for posterity, Nixon was making amends for Dulles’ crude behaviour in Geneva. And that shaking of hands by Nixon and Zhou was a harbinger of seismic change in global politics. China today is that giant which has risen from slumber and strides across the world in all its growing power.

The history of handshakes tells us of other men who have conducted themselves in crude manner. In the 1940s, as India hurtled towards partition, the leaders of the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League held quite a few meetings to iron out the details of the coming separation. At one of the meetings, Mohammad Ali Jinnah shook hands with Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and other Congress leaders. But, in a moment of terribly bad judgement, he refused to shake hands with the scholarly Moulana Abul Kalam Azad. For Jinnah, always the epitome of arrogance, Azad was a Muslim showboy of the Congress. When you study history today, you are not surprised that Jinnah is a man almost forgotten and Azad is respected worldwide for his political acumen and moral wisdom.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a day after the Agartala conspiracy case was withdrawn and he and his co-accused were freed unconditionally by the Ayub Khan regime in February 1969, travelled to Rawalpindito attend the Round Table Conference convened by the president. Ayub Khan and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been in mortal combat for a decade, with the latter endlessly subjected to gross ill-treatment by the former. At the RTC, all heads turned to see how the two men would approach each other. President AyubKhan extended his hand to his former prisoner; and Bangabandhu reached out to take that hand. It was a reaffirmation of the lesson that in politics, you do not let personal feelings stand in the way of public conversation. For Bangabandhu, this business of shaking hands with men who tried to do him in would go on. On the night between 25-26 March 1971, once the Bengali leader had been taken prisoner by the Pakistan army, General Tikka Khan disdainfully spurned the idea of having Mujib brought before him. “I don’t want to see his face”, Tikka said in contempt. Only three years later, as Pakistan’s army chief, he was saluting Bangladesh’s founding father at Lahore airport. A smile wreathed in sarcasm played all over Bangabandhu’s face as he shook hands with the general who had unleashed Operation Searchlight against his people.

Bangladesh’s founder was to shake hands with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto for the first time after the liberation of Bangladesh when Pakistan’s new president went to see his country’s famous prisoner at a rest house outside Rawalpindi in late December 1971. The two men were to shake hands again in February 1974 when Bangladesh’s leader flew to Pakistan to attend the Islamic summit in Lahore. In 1967, at the height of the Cold War, US President Lyndon Johnson and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin met and shook hands at the Glassboro summit. As the war raged in Vietnam, an embattled Johnson sent his envoy Averell Harriman to Paris to open negotiations with North Vietnam’s Xuan Thuy. When Richard Nixon succeeded Johnson, he despatched his national security advisor Henry Kissinger to Paris to negotiate a settlement to the conflict with the hardened Vietnamese communist politician and intellectual Le Duc Tho. Both Harriman and Kissinger, driven by the compulsions of history, needed to shake hands with their interlocutors.

In January 1966, at the Indo-Pakistan summit convened by the Soviet leadership in Tashkent, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and President Ayub Khan entered the hall simultaneously through two different doors, walked up to each other and shook hands before getting down to business. Six and a half years later, President Bhutto, having vilified Indira Gandhi over the years, found himself in Simla shaking hands with the Indian leader as they both prepared for talks in the aftermath of the Bangladesh war. In the 1940s, the Indian nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose, desperate in his struggle for his country’s freedom, saw little reason to keep Adolf Hitler and Hideki Tojo at arm’s length as he solicited overseas assistance against the British. He shook hands with Hitler in Berlin and then with Tojo in Tokyo. It is another matter whether Bose should have consorted with these men, one of whom was ravaging Europe and the other was destroying all of East Asia.

Our very own Tajuddin Ahmad refused to have anything to do with World Bank President Robert McNamara at a meeting in Delhi in early 1972. Over two years later, he travelled to Washington, shook hands with McNamara and got down to a discussion of conditions in Bangladesh. In November 1977, Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat made history when he flew to Jerusalem in the night in search of peace with Israel. His handshake with Israeli leader Menachem Begin remains a defining image of the times.

The very conservative Ronald Reagan shook hands with the very liberal communist Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva in 1985. Nelson Mandela shook hands with F.W. De Klerk in 1990. Neville Chamberlain, before he was double-crossed by the Nazis, shook hands with Hitler, reached a specious peace deal and came home to London to tell his people that peace had been achieved ‘in our time’.

Shall we now give our hands a little rest?

— The author, Syed Badrul Ahsan is an independent journalist and political analyst